Since Jess’ death, it has taken me a lot of time to sit with what has been said, left unsaid, folded into the humdrum of each day. I think I have been trying to write to her with each passing day, but my words hang empty in the air. Loss operates in this funny way—as Lauren Berlant notes, it both approximates and distances. So, after many drafts, I decided to create a mosaic of what I know for certain, which is the specific quality of my life and how it orbits people like Jess. Although our budding friendship was cut short by Jess’ untimely passing, I felt and still feel an affinity toward her presence.

Here, I borrow words from friends and theorists that I love as to attempt to reach Jess, and by extension, her ideals. I also write this piece to discuss what Kevin Suemnicht calls, in their piece on Ill Will, a vital cell. Drawing from Suemnicht, I want to think of the vital cell as a rhizomatic group that is the result of turning elsewhere. Berlant, in their book On the Inconvenience of Other People, writes that "The protagonist's dissociative sensorium sees the world and is in it, and at the same time has turned elsewhere—because it must, because it needs to, because it did, or to test out ways of flourishing."1 This flourishing is what draws me in, what makes me think of people like Jess. How do we negate the forces of biopower that have made our lives to a living death? How can we want the world without wanting to live it in?

For the first time in my life I found myself in unfamiliar August heat—it clung to the skin like a film, or a powdery residue. I had just returned from visiting my father in Greece and, by that time, was used to the briny Mediterranean air. Jet-lagged from a long flight, I grabbed a stool from the co-op’s kitchen and sat under the sun. The light was a little too bright for my tired eyes. And, what’s more, I had never realized before how brilliantly green late summer in upstate New York was. There, the verdant bloom, and beside it, the heavy crowns of towering sunflowers. They were perched on the old barn’s awning like keening birds. I was taken. Behind me sprouted a chorus of voices and laughter. By nightfall, all of my new friends and I had prepared curry, chapati, and chutney from scratch. Our illuminated heads formed a corridor along the long dinner table.

At the end of the table sat Jess. She was smiling as she held her daughter, Willa, in her arms. Willa was positively cherubic, a curly haired toddler with a penchant for graham crackers and frogs. She still struggled to pronounce the dog’s name, Apollo. Every time he came around to give her a lick, she’d excitedly squeal “Allapollo!” I looked all around me—among the clinking silverware and political ideas, I felt like I had become rhizomatically embedded in this special world—the way mycelium extends its root-like structure and forms a network of communication and nurturing. This, I thought, is what communion must be like. We had made this other world in response to the limit of life. In private, but still in the presence of other people, I wrote poems. The following is a poem scribbled on a torn piece of paper:

HOT HONEY

Bold bads! yells Undeniable across the dinner table. We brim with laughter and spill grains of fried rice. We are born

together. It is, for a moment, the twittering of desire. Desire is the bunch of cherry tomatoes at the edge of my sight.

Everyone is more beautiful than I could hope to be. Disbelief sits next to me and mixes hot

honey into their meal. I hold down Apollo’s leash as he lunges toward an unsuspecting frog.

What else do we know? We are all things that have been. Chiseled beam, puff of hydrangea, striated squash.

O’ mess, O’ communion

A cloud of arms pantomime fullness, mischief. We rush to the meadow’s clearing and paint the night. I call this high fidelity. This need for badliness—as if all violence is the means of creation.

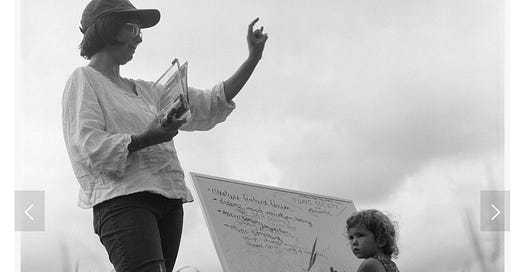

When I moved from Los Angeles to New York in the summer of 2022, I was worried that I would have a difficult time integrating in the local community. My political commitments often tossed me into the throes of fractured leftist politics. While our organizational efforts were usually fruitful, there was always too much bickering, too much arguing. There was also a lot of hurt and death. My comrades and I are well acquainted with the faces of loss, fear, and destitution. But even so, we always try our best to coalesce into small groups and carve out spaces that are not subject to normal social impositions. This is why people like Jess are important: she had been the one to call for an ‘otherworld’ experience for all of our comrades.

The point of gathering at a farm in upstate New York in the thick of August was to remind ourselves that what connects us is a hybrid form of political and environmental vitalism in our uncertain present. We were also well aware of what Berlant calls "autopoietic death"—our deaths, the deaths of our comrades were "a looming consoling and threatening event."2 Our time at the farm was spent foraging, bathing, and talking together. And, even though our lives and deaths were embedded in the uncertain present, we were not concerned with who identified with what, with whatever niche ideological pursuit. At night, we made delicious meals and sang together a song that we’d eventually chant at Jess’ memorial a year later. The uncertain present that perforates the fabric of our lives brings me to what Anna Tsing, in The Mushroom at the End of the World, calls “precarious livelihoods and precarious environments.” She writes:

In each case, I find myself surrounded by patchiness, that is, a mosaic of open-ended assemblages of entangled ways of life, with each further opening into a mosaic of temporal rhythms and spatial arcs. I argue that only an appreciation of current precarity as an earthwide condition allows us to notice this—the situation of our world. As long as authoritative analysis requires assumptions of growth, experts don’t see the heterogeneity of space and time, even where it is obvious to ordinary participants and observers.3

For us, the heterogeneity of space and time is a given. It expresses all of the loss and pain we have experienced, as well as the joy that we are capable of feeling in each other’s presence. This is precisely why there is a need for collaborative survival and the analysis of capitalist destruction. Insurrectionary movements involve a rhizomatic development and they form an assemblage. The word assemblage describes their liveliness and complexity—a complexity that cannot simply be observed by way of what Tsing calls an authoritative analysis of growth. Assemblage is what results from rhizomatic growth. It is not something that one assembles, rather, it is something that emerges with the right kind of care and attention. We do not make assemblages, we tend to them.

During the last decade, I have been enmeshed in various political causes which have connected me to the most beautiful (but politically divisive) people that I have ever met. Wherever I found myself geographically, I always orbited individuals whose sole purpose was to make the world we live in more hospitable. These friends embody the insurrectionary ideal. And although many of them have differing opinions, they are the gardeners who tend to the assemblages that germinate in every part of the world and that have dissociated themselves from biopolitical realism.

Tsing relies on the word assemblage to describe the ‘situation’ of our world, what is consistent across the heterogeneity of space and time. Here I want to lean into the concept of the vital cell, which was coined by Jess’ friend and comrade Kevin Suemnicht. The notion of the vital cell emphasizes the organic, unruly body of contemporary revolutionaries—our body is one that is alive, yet like all cells, is proximal to death. It exists in a dissociative state, and within its death—its programmed suicide—"becomes a way of life for the subordinated in exhausted submission and resistance to wearing out."4 Even though Jess did not use this specific language to describe what she was doing, she recognized that the assemblage/vital cell was what’s at stake. This is why she put in so much effort to remind us that we were alive, and that we were also close to death.

The term vital cell is meant to illuminate the fundamental organizational and socio-emotionally attuned attributes of revolutionary movements. Berlant also mentions that the focus of their work is on how we can feel out “... the moments of living the inconvenience of being an imperfect and flailing subject, whose debilitating and desiring moods force them to generate alternative forms of getting through episodes and existence that allowed for continued attachment to life.”5 Jess was deeply interested in how people “... generate spaces of alternative life alongside threat and breakdown.”6 For her, the vital cell is exactly this. The Otherworld, with all of its bubbling intensity, its laughter, its tears, its warmth and its unyielding existence, opposed the way that 21st century politics move on unabated.

Beginning two years ago, insurrectionaries have been gathering in the Weelaunee Forest in Atlanta, Georgia, to save the land from the development of the so-called Cop City. Starting in April 2021, various political movements have made it their goal to defend the forest from being uprooted. What is currently happening in Atlanta is paradigmatic of the repressive, regressive, and fascistic regime of the United States. In building a cop compound, they are actively militarizing an already violent and largely rogue state apparatus that is trying to impose its biopolitical power. While the Weelaunee Forest is indicative of what might be a bleak future, the struggle there has also propagated the nascent stages of the vital cell. It has demonstrated that there is a life that is everywhere, a dissociative life that insinuates an ongoing existence. As Berlant writes,

By dissociative life I mean a life lived in intimate relation to life in a lifeworld that is also, and at the same time, apprehended ambivalently, from engaged distances, in an affective structure where inhabitants dwell in detachment that does not signify an absence of feeling.7

Although the vital cell is literally and figuratively detached from the biopolitical reality, it is swelling with affect and revolutionary emotion.

Revolutionaries of all political backgrounds, races, ethnicities, ages, gender identity and ability have come together in Weelaunee forest to meticulously assemble. All of these people are considered to be inconvenient by the systems in power. Much like the farm I visited in upstate New York, the protesters against Cop City have lived symbiotically for the last two years, integrating themselves into the land. There are the tree sitters, the ones who forage, there are the others who pitch tents in front of work sites. There are also those who linger by the river alongside the trillium and swaying birch trees. Finally, there are many Jess’s—individuals who have already noticed the need for the proliferation of a biological negative feedback loop, for the development of a vital cell.

In January of 2023, Georgia state troopers shot and killed Tortuguita, a 26 year old Indigenous, queer protester who had been living in Weelaunee forest for some time. The immediate news coverage following their murder promoted a false narrative of self-defense on behalf of the troopers who shot them. GBI officials argued that Tortuguita had a gun and was first to fire–in response, the troopers shot through their tent and instantly killed them. When I visited Tort’s memorial in Weelaunee shortly after their death, I was amazed to see the amount of people who had come to pay their respects. We sat near a makeshift vigil late into the night and played songs on the guitar. People I did not know slung their arms around me. We chanted “Tortuguita Vive! La Lucha Sigue!” over and over until our vocal chords tremored.

Among us, unsurprisingly, there were undercover police officers who had been sent to monitor our interactions and behaviors. To me, this indicated a clear fear of the vital cell: the government, perhaps for the first time in a long time, felt threatened by the liveliness of the dissociative revolutionary body. And I mean dissociative in the most basic essence of the word: according to the OED, dissociation means “To cut off from association or society; to sever, disunite, sunder.” They were afraid of the world's ability to "... [generate] unincorporate spaces whose patina emerges from a collective imaginary's work and not just the projections onto it." Later, in April, the state released Tort’s autopsy. The report verified what the insurrectionaries already knew. There was no gunpowder residue on Tort’s hands, and they had died sitting cross-legged, with their hands raised. They had been shot 57 times. I often wonder if, in their last moments, they hoped to see the crown-shyness of the trees above them—that unrelenting sun.

A few months after Tort’s murder, Jess would be diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer, and, within two months, she would pass. Like Tort, Jess’ memorial drew a myriad of people in. It almost felt like vertigo to be surrounded by so many people. They shared stories around a fire until the darkness descended upon us like a shroud. Then, one by one, we lit candles and sang the following:

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

I don’t remember most of the stories that people shared—my mind was too clouded. What I do remember, though, is how the treetops danced above us, how the hot wax burned my fingers. Even after her death, Jess had created for us a most precious circumstance; she had given us the ability to coalesce and be with each other, to want the world without wanting to live in it. And the truth is that we didn’t have to live in it. In those moments, we were the world. Our vital cell was the world, and we were alive.

Thank you, Jess, for giving me the gift of yourself.

Images: Katherine Finklestein

Berlant, Lauren. The Inconvenience of Other People. Duke University Press, 2022. 123.

Berlant, 122.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton University Press, 2021. 4.

Berlant, 122.

Berlant, 120.

Berlant, 122.

Berlant, 133