Sabotage

Beyond the mega-basin, the horizon

Preface

We are excited to publish this pair of report-backs and analyses of recent actions by our friends in the movement for environmental justice in France. They strike us as an exhilarating example of all that has gone well in the movement up until this point and chart a path forward we hope others can imagine walking themselves.

As is well-known, the rising tide of struggle against global warming responds in many cases to literal rising tides. The resulting horror for many people—especially in the global south—is that there will be too much water for life to go on living. As the surface of the earth warms and the arctic begins to see rain rather than snow, the oceans threaten to swallow whole islands, whole regions, whole coasts. For others, the problem is quite the opposite: wildfires, severe droughts, creeping deserts, and massive species-extinction. Although located in a "safer," more temperate zone in the European center, France nonetheless belongs to the latter group. The last few years have seen a terrible drought, so bad at times that wildfires rage across the southwest and nuclear power plants must be shut down for want of water with which to cool the reactors.

This drought has been especially difficult for French farmers, who struggle to maintain sustainable crop yields in the absence of rain. In response, the French state has imposed broad restrictions on water use and begun to construct a series of mega-basins, enormous artificial reservoirs designed to draw the region’s groundwater to the surface and make it available during the hot summer months.

In its natural state, groundwater functions as a sort of subterranean agricultural commons, protected from solar evaporation and, at least in part, from different kinds of industrial or atmospheric pollution, such as runoff from factories or the life-cycle of other organisms (like insects or animals). Once drawn to the surface and encased in concrete, the water changes shape entirely, becoming a “resource” to be allocated according to the ends and interests of the state and its partners. When the state proposed the construction of sixteen more of these basins in 2017 in the Deux-Sèvres department, they offered 60 million Euros of government money to pay for the project, and promised the en-basined water to a specific cooperative of over 200 farmers known as Water Coop 79. While restrictions on water usage extend to everyone, only those who partner with the state have access to the mega-basin reserves, transforming the groundwater from a vital commons serving all life and even the land itself into another kind of private property.

This expropriation of the groundwater is by no means necessary or permanent, as the actions described below demonstrate quite clearly. The first action described, which occurred just ten days ago, attacked and sabotaged the Lafarge Cement Factory, where the cement needed to construct these mega-basins is produced. The second, the massive rally against the construction of the mega-basin Saint-Soline back in August, brought together a thousands of different people and a coalition of organizations to bring work to a halt for over a week. Both actions not only interrupt the expropriation of the water commons or the cement production essential to agribusiness but introduce a whole different horizon of a life lived in common with all living things, from the wetlands of France’s Green Venice to the bustard flying over small farmers’ fields of rapeseed. Les Soulevements des Terres describe this horizon in the final lines of their website:

We are young rebels who have grown up with the ecological disaster in the background and precariousness as our only horizon. We fought against the labor law, police violence, racism, sexism and the climate apocalypse.

We are inhabitants in struggle attached to their territory. From legal recourse to direct action, we have achieved local victories. Faced with the concrete builders, our resistance is multiplying everywhere.

We are farmers. There are almost no more in France. We strive to establish a relationship of daily care to the earth and to the living to feed our fellow creatures.

We are: you, me, us. All those who feel isolated and powerless in the face of the atomization of struggles, the difficulties of acting, and the voracity of the owners. Those who were waiting to be more numerous to fight: here is an opportunity to join our actions and our reflections, this is the moment!

Like the Zapatistas fighting for the right to a life lived in common and a world in which many worlds fit, like our indigenous comrades fighting the construction of pipelines across their reservations and burial grounds, like our friends sitting in trees and fighting charges of “domestic terrorism” in the Atlanta forest, like the joyous masses who burned down the Third Precinct during the George Floyd Rebellion, we, too, are part of these uprisings of the earth. And so we hope you'll read these pieces as the invitations that they are, to join in the uprising and fight for a horizon of life that sacrifices no one.

In Marseille, the Lafarge Cement Plant Invaded and Sabotaged by 200 Militants

Originally published in lundi matin

On December 10, 2022 at 6pm, 200 people invaded the Lafarge plant of La Malle in the city of Bouc-Bel-Air, taking the plant by surprise and disarming it. With a determined and joyful atmosphere, the infrastructure of the plant was attacked through any and all means: incinerator and electrical devices sabotaged, cables severed, bags of cement eviscerated, vehicles and construction equipment damaged, office windows ruined, and walls repainted with tags.

Lafarge-Holcim is one of the largest polluters and CO2 producers in the country. Targeted by several anti-terrorist legal proceedings, the multinational corporation systematically stifles any attacks against it. Here in Bouc-Bel-Air, the furnaces we’ve targeted, long fueled by tires and other industrial waste, are now a symbol of greenwashing. Though the atmospheric pollution is considerable and has been denounced time and again by the press and by local residents, the chimneys still spew their poison.

For three years, more and more determined actions have targeted Lafarge-Holcim in France and in Switzerland. First, there were the "Fin de Chantiers” blockades in 2020, followed by the simultaneous occupation and sabotage of four sites by hundreds of people in June 2021 during the "Grand Péril Express" operation, and finally successive mobilizations against the destruction of the Saint-Colomban bocage by Lafarge in the Loire-Atlantique region of France and the Zad de la Colline against an extension of Lafarge's quarry in Switzerland.

Footage of the Grand Peril Express actions in June 2021

After the bitter failure of the COP27, a failure easily foreseeable in the current COP15 in Montreal, we didn’t want to wait for a COP 2050 and another three degrees, so we returned today aiming at giving ourselves right now the means to stop these construction industries that destroy the earth.

Lafarge and its accomplices hear nothing of the anger of the generations they leave without a future, in a world ravaged by their misdeeds. Their machines, silos and concrete mixers are weapons that kill us. They will not stop unless we force them to. So we will continue to dismantle the infrastructure of disaster ourselves. We call on all those who stand up for the earth to occupy, blockade, and disarm concrete.

Why target Lafarge?

In its delirious race for profit, the Lafarge-Holcim group, along with its billions in revenue, refuses to back down, in disregard of all the ecological and social consequences it generates. Prosecuted in several countries, Lafarge and its leadership have demonstrated their cynicism through their involvement in financing the Islamic State in Syria. Sentenced by the United States in October 2022, and fined to the tune of 778 million dollars for supporting Daesh, they are still under investigation in France for complicity in crimes against humanity. The succession of tactical choices made by the French state, seen in exchanges between the DGSE and Lafarge, demonstrates one time too many that the proper functioning of capitalism requires that the state and industry work together.

Extracting rock under the protection of the State, even if it means feeding the war. Selling cement to rebuild what the wars have demolished. And in the process, destroying our living conditions and our environments to build a world of concrete and death, whether through greenwashing based on carbon neutrality or low-carbon cements produced by incinerating waste.

From the extraction of sand, to the production of cement and concrete, and to the massive, useless projects it facilitates, the entire complex of the construction industry represents an ecological catastrophe. From its supply chain to its application, the construction sector is responsible for 39% of CO2 emissions worldwide.

Here in Bouc-Bel-Air, Lafarge has never hesitated in lobbying for an allowance to exceed the environmental standards for dust and sulfur oxides set by the European Union. Of the fifty most polluting sites in France, twenty are cement plants, including this one, which produces more than 444,464 tons of CO2 per year, and feeds its kilns with thousands of old tires and all sorts of other toxic waste.

Within our landscapes as well as our imaginations, concrete has become the norm under the pressure of the industry’s lobbying and the complicity of public authorities. It is at the heart of the most absurd projects of the last decade: the construction of the Greater Paris Express and the 2024 Olympic Games sites, the attempted airport at Notre-Dames-des-Landes, the extension of the Château-Gontier quarry in Mayenne, or a few kilometers from here, the paving over of agricultural land in Pertuis....

Since power tightens its grip on its resources and its massive projects, even inventing the term eco-terrorism to legitimize its tracking of environmental activists, since today nothing seems to stop them, we will stop them ourselves. Discovering an adequate means to put an end to the ecocidal projects of land development, and destroying the infrastructure that makes them possible, are the only options to make the world desirable once again.

We do not want colonial eco-capitalism, a war-time economy, or a cynical and manipulative ecological transition. This is why we attacked Lafarge-Holcim today.

Bouc-Bel-Air, December 10 2022

Some Lessons From Sainte-Soline

Originally published in lundi matin

There has been a great deal of discussion in France about this demo against the mega-basins in Saint-Soline from October 29 and 30, and for good reason. The diverse and energetic crowd routed over 1700 police officers and six helicopters, much to the ire of the Minister of the Interior, among others. We feel this moment has as much to teach us as it did our friends in France, and we are therefore happy to bring you these lessons those involved published two weeks after the action. It offers lessons of great importance to those struggling against the end of the world everywhere.

"I was thinking again last night that I was missing something to take out the garbage.”

- Anemone, actress and temporary resident of St. Soline

Two weeks have already passed since the demonstration on the red lands of Sainte-Soline against the construction of the second mega-basin in Deux Sèvres. Marked by such enthusiasm that we have yet to wrap our minds around it, the demo continues to command both media and political attention. But after this period of forced work stoppage, the government has opted to resume construction and promised to build thirty new basins in the neighboring department.

The next national date of action will be announced this Thursday. These actions will aim to have a more lasting impact on these projects, putting them to a definitive end.

While waiting to organize ourselves accordingly, we want to share some considerations on the lessons to be learned from the October 29 demonstration, based on the path we have taken over the past year with the movement. We want to believe there is something to be learned from this experience that is more tangible than the projections emitted by the crowd of parachuting experts who lined up to speak to the media afterwards.

What we seek to explore here revolves around the following two hypotheses:

Starting from a given region and a relatively new form of infrastructure, which its promoters plan to spread everywhere, it is possible to unravel the knot tying together water monopolization, the maintenance of the agro-industrial complex, and the current unwavering support offered to it by the State. Therefore, there are two opposing horizons for the concerned territories, with a barricade between them, the two sides of which continue to be clarified, and some possible turning points in the face of the climate crisis.

More than an action of ecological resistance that suddenly increases the balance of power in a specific struggle, the action in Sainte-Soline engages in the necessary reconfiguration of the political field. Its offensive texture—comprised of teenagers grown up in a shipwrecked world and of lovers of the little bustard, of debaucherous rioters and retired people whose age has rendered them all the more diehard, of trade-unionists rediscovering their taste for sabotage and elected representatives, for once acting courageously. This breadth of the struggle gives a glimpse of what moments of climatic revolt could be, of the way they should take shape everywhere from now on in response to the absolute emergencies of the time.

Reflecting on the movement’s rising force over the last year

The strength experienced collectively in Sainte-Soline is an event in itself, while also being the result of the actions which preceded it. Before questioning its scope more precisely, we need to put it into perspective by summarizing the sequence of events that led us to the storm of the Red Soil.1

More than a year ago, a site equivalent to that of Sainte-Soline was already invaded and damaged. It was the lunar crater of the mega-basin of Mauzé-sur-le-Mignon, on the edge of the Poitevin marsh. This was the first in a series of sixteen structures that the prefecture and the groups of irrigators wish to build in the department. With the start of construction and after years of all kinds of mobilizations, information nights, and legal appeals—all necessary, but obviously insufficient in the eyes of the government—construction began and the local coalition Bassines Non Merci saw that it was necessary for the struggle to pass into another stage. A convoy of farmers from Loire-Atlantique shifted the narrative framing produced by the opposing camp, showing that this was not simply a fight between environmentalists on one side and farmers on the other, but rather a split between two possible agricultural horizons. The thirty tractors, joined in Niort by a few hundred people, took the police by surprise when they suddenly rushed towards the basin, some fifteen kilometers away. Once the gates fell, the crowd (accompanied by a band of sheep) joyfully put one of the excavators out of action after it was abandoned by its driver. Meanwhile the local spokesperson of the struggle announced in front of the cameras that "for every one basin constructed, there will be three destroyed." This intrusion on the construction site was a powerful assertion of the vulnerability and the barren materiality of this infrastructure, as well as of the new phase of the movement. This meeting in action between three distinct groups—Soulèvements de la Terre, Bassines non Merci and Confédération Paysanne2—called for a rapid follow-up.

One month later, 3,000 of us gathered in the town of Mauzé, this time finding a massive deployment of police determined to prevent us from reaching the construction site, which was itself occupied by the troops of the FNSEA who had come to defend their hole. This first big showdown gave birth to Episode One of "The Taking of the Basin," by way of a concerted detour from the site we had initially targeted, leading us instead to the neighboring and already existing basin of Cran-chabam, which was opposite the mass of police and opposing troops. Accessing it was a matter of passing through lines of gendarmes, crossing a stream with several thousand people, running through fields, piercing gates while being shot at with grenades, all before reaching the big crater, dismantling its pump and removing its plastic tarp while dancing around a pirate ship. Ten days later, faced with the cries and threats of repression from the government and the FNSEA, a number of public figures and national representatives associated with various political and trade union organizations, most of whom had not yet set foot in the Deux-Sèvres, came to affirm the need for "disobedience" and to support the uncovering of the mega-basins. This confirmed that a front had been created around the defense of water, one that was both widely supported and determined to give itself the necessary means to stop the construction sites. It was also a second slap in the face for the prefect of the Deux-Sèvres, who left a few months later and was replaced by Emmanuelle Dubée, who was tasked with putting an end to this struggle.

In spite of these two first mobilizations, the construction of the SEV 17 (the shorter technical name of the Mauzé basin) was in the end completed, though at a considerably higher cost owing to the need to ensure the continuous surveillance of the process. But in the meantime, the brazen punch thrown at the gendarmes on the Mauzé site had obviously been taken quite seriously. Between September 2021 and September 2022, nearly ten existing basins were indeed dismantled at night by various groups with evocative names—the "Rolling Cutter Gang," the "Fremen of the Poitevin Marshes," or the "Angry Rivers"—groups who had all decided to reinforce the impact of the public mobilizations in their own way. With ten basins destroyed for the one built, the tension3 was palpable in the Poitou.4

The movement’s next public incarnation was another rally in March of this year in the small village of La Rochénard, still with the SEV 17 basin in the line of fire. On this occasion, 2,500 gendarmes were mobilized and the demonstration was forbidden to enter within a perimeter of several square kilometers. This did not prevent 7,000 people from braving the checkpoints to converge on the camp. This record mobilization was a crushing rebuttal to the few voices who claimed that more determined actions would risk isolating the movement and "discouraging the masses," said masses being obviously rather satisfied to be able to take part in directly impactful demonstrations. Once again, everything possible was done to prevent the approach of the site. Gendarmes were deployed on foot, motorized teams in the fields, helicopters overhead, and above all, increased pressure from the local prefecture services and agricultural authorities on the Confédération Paysanne, which had publicly announced the event. The dilemma faced by participants that weekend was whether it was necessary to enter the forbidden zone or to change the target. The second option was chosen, in part due to trepidation regarding the possibility of arriving together at the original site, but also because the alternative action—taking pickaxes to pipes intended to feed a future project—allowed the movement to extend its domain of tactical competence. This new gesture pointed beyond the site of the basin itself and towards the tentacular and thus indefensible character of this type of infrastructure. Cutting a tarpaulin, a pump, or pipes with an electric saw became so many small, simple, shared gestures that prefigured the disarmament of all the existing basins and drenched their promoters in a cold sweat.

Our slogans no longer appeared as empty threats: if they started a new construction site, we would come and stop it four weeks later. The clarity of this objective did not prevent more than 150 organizations from joining the call. And by the beginning of October, as soon as the first grids were laid around Saint-Solin, the preparation meetings were in full swing and a map of the companies involved in the project was published. For months now, the territorial network of Bassines Non Merci has continually amazed us with its connections to people in different trades and social strata, which have relayed material solidarity and sources of information.

In the immediate perimeter of Sainte-Soline, the ground is at first sight much less conducive to conflict than around the Poitevin marsh, the cradle of the struggle. The local irrigators and prefecture put significant social pressure on the movement’s supporters, at first hindering the search for sites of convergence. However, a few well-attended public meetings allowed the movement, step by step, to find openings. A huge field less than 3 km from the construction site was discreetly proposed by its owner, himself a former irrigator who had broken with the basins and decided to make this courageous gift to the movement. While two unions called for the demo, the logistics team stayed one step ahead of its quite predictable ban, preparing the surprise installation of a camp which would arise within a convoy of trucks and tractors in the heart of the forbidden zone the day after its location was declared by the local government..

The standoff began on Tuesday when the first tents were pitched, while the landowner explained to the media why he had decided to switch sides and invite his former opponents to camp on his land. This moment initiates a chain reaction: the prefecture raises its tone, but can hardly find a legal ground on which to expel us directly; it extends prohibition orders all around, emptying the site of its machines and redoubling its threats in the hope of dissuading the demonstrators. But the first images of the camp go viral, attracting more opponents of the basins and haunting the authorities, who are obsessed by the specter of the construction of a zad,5 a mirage that undoubtedly aided in the media surge. When the ban on movement in the red zone went into effect on the eve of the demonstration, a critical mass of more than 1,000 demonstrators was already occupying the area.

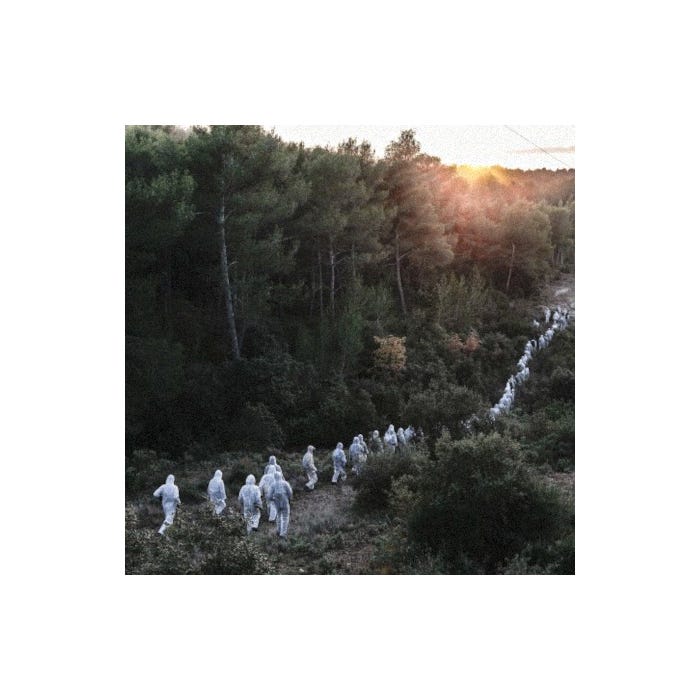

At 7am Saturday morning, the cat and mouse game begins. But the fields and dirt roads of the countryside around Melle are full of passages impossible to close off entirely, especially for those who are willing to walk a little with a small map in hand. A communication apparatus combining an info line with reception points in the surrounding villages allows more than 6,000 additional demonstrators to join the camp.

First victory of the day. The tarpaulin trucks and the police vans are already positioned on departmental road 55, which separates us from the construction site, supported by six helicopters. Faced with them, we will respond with a game. Between 10am and 2pm, several teams go through the crowd distributing a leaflet entitled 1,2,3… Basin! Inside it, one reads a proposal to divide into three processions and to try to melt, taking different routes and assuming different attitudes, towards the target and to bring down the fence enclosing it.

Almost instantly, all the participants agreed to play this game, forming three groups of several thousand people. The lines of gendarmes, visibly disoriented by the ardor of these processions, are re-routed in all directions as their narrow set of tactics singular deployments are overtaken by successive waves of farandoles, chains, races, or volleys of projectiles. One team, the reds, supported by the mobilization and advance of the other two teams, manages to enter the site en masse for a few minutes before planting its flag. They take down a good portion of the fences, which effectively stops the construction from resuming for some time. Shortly after, the three processions meet in front of the basin’s construction site for a snack interrupted by shots of flash-ball grenades. We have just witnessed Episode Two of the "Taking of the Basin." The next day, a pipe intended for use in filling the basin is dug up and disconnected by hundreds of people around a pickup truck marked "freewheeling irrigators," broadcasting maloya music. We then celebrate the dismemberment of one of the arms of the octopus and the exposure of its underground tentacles.

The government unilaterally announced that the movement’s intention was to create a zad, in order to claim, in spite of everything, that it had succeeded in preventing something from happening. But instead of a zad, a simple altar was left on the field. We know we can come back or redeploy elsewhere. Ten days later, when construction is restarted and a protocol for the building of thirty new basins is signed in the neighboring department of Vienne in the middle of the COP 27 climate conference, nobody doubts anymore that the government is locking itself into this course of action and that the Sainte-Soline demonstration will have consequences. Elaborating those consequences in the aftermath of this turning point requires us to question the scope of the fight.

What Sainte-Soline offers to us

While this struggle has been going on for many years, over the last year it has seen a considerable acceleration as it appears central to the question of water and its distribution. About fifteen years ago, roughly twenty basins built in the Vendée department experienced no resistance. What is the difference today? Along with the ratcheting up of tensions after years of successive droughts, there is also the blossoming of years of struggle by the inhabitants and neighbors of the Poitevin marshes against the agro-industrial desert that threatens to dry it up definitively. First and foremost, what gives substance to the struggle in the Deux-Sèvres is the real, concrete, and irremediable link that they forge with the waterways, with the non-human populations that inhabit them and fly over them, and with the land that surrounds them.

If this united front is possible, it is because even where the seemingly unlimited fields of productive agriculture no longer extend, there are still people, places, and recesses that form a community connected through the anger caused by their devastation. For those who come to support them from farther away, it can sometimes be a matter of giving back to those from the marsh who, a few years earlier, regularly traveled hundreds of kilometers to save other wetlands. For all of us, it is now a question of finding a common grip, of converging around a target embodying the ways the profound upheavals our planet is undergoing are being imposed upon us, and of pulling that thread all the way to its end. At the heart of the "disaster," as it is called, are the readjustment measures by which power attempts to regulate (and prolong) the catastrophic situation it has itself perpetrated. Beyond their evident specificity, the mega-basin projects are emblematic of this broader logic: perpetuate for a few more years an agricultural model that has run its course, until there is not a drop of water left. Then we'll see. Opposing the basin projects allows us to recapture the need for a front of active resistance by taking hold of the climate change angle and carrying it forward from this point. It is a way to re-interrogate the practices of all those who for decades have been trying to act in the name of political ecology.

The problem with what we generally agree to call the "ecology movement" is that it is paradoxically both constitutive of our own political history, but too often captured by the opposing apparatuses, and has tended towards defeat for several decades. Any victories it has achieved, however notable, remain scattered. It must now enter a period of substantial success or sink with the world that it has failed to save.

It is difficult to define the possible horizons of this movement. There are those who expect the State to act genuinely in the direction of the "ecological transition,” those who want to take the reins of power, those who seek to give the movement a nonviolent identity, to make it carry a revolutionary hope, or to refuse this pretension absolutely. There are those who fight above all against a local development project, those who seek to defend another agricultural model, and those who essentialize the question of “nature” and through that concept, reactualize the most nauseating and fascist ideas in history. There is no unified “ecological movement” today.

While there is no need to try to put everyone in agreement on the theoretical plane, it is still necessary to take note of the strategic and sometimes even political and philosophical differences that separate us, all while anticipating what the real movement will transform.

The more tense the climatic and social situation becomes, the more it seems to take away our capacity to act. It is a phenomenon that is perplexing, to say the least, until we find its point of reversal. There is a kind of resignation in the air that the complex heritage of ecological struggles has not yet mitigated in the realm of theory. We seek to overcome this resignation with a certain pragmatism, among other things, beginning from the tangible grounding of the Poitevin marsh and the complicities we have found there. Our wager today is that the construction of this game of complicity will allow alliances of circumstance to transcend the contours of strict ideology and militant conventions.

The most recent person to have paid the price is the prefect of Deux-Sèvres, who we are surprised to see still in office after the slap in the face she suffered. The whole arsenal of Republican law and order was assembled with the aim of making it impossible to lift a finger ten kilometers around the site. But everything that was not supposed to happen did happen. The arrival of Darmanin to the rescue—using big words to channel the attention of journalists and promising, for once, the utmost firmness—did not change anything. At his side is the expertise of a high-ranking general (Richard Lizurey, who coordinated the eviction operations on the zad at Notre-Dame-Des-Landes in 2018) who reduces the conflict to a simple question of militarization of the so-called radicals, as if desperately seeking to justify their rout by putting 1,700 overarmed gendarmes aided by unprecedented air support on equal footing with a few thousand demonstrators equipped with stones gleaned from the fields and some fireworks. More than ten years of repression and police mutilations against the zads, along with the Yellow Vests, allow us to understand this umpteenth lie, behind which the authorities of this country hide. They decide to bruise flesh in revenge as the gates of Sainte-Soline fall, even at the risk of replaying the nightmare of Sivens, all under the pretext of defending an empty building site. But the damage has been done, and no matter how important the caricatures of debates on violence become, the issue of water-hoarding is now front and center, and the coming droughts will not help to ward it off.

To push the government back more definitively, the anti-basin movement will have to continue to aggregate. History has shown us that growing a capacity for force almost systematically implies adding a fairly extensive diversity of practices of struggle and actors to its repertoire. But the diversity in question must not become the heart of what brings us together, nor even the collective objective. We must first elaborate and share a certain tactical sense of emergence, a way of taking advantage of the different tools that our predecessors have passed on to us, and reinventing them as often as necessary.

So far, the political forces at the heart of this struggle are not seeking to contain or overwhelm each other. Rather, their attention is entirely focused on what will impact the opposing apparatus and bring about unexpected arrangements—with the now emblematic collusion of masked groups, peasants and elected officials in scarves, teens and old-timers, all of whom strike at the same target. Together they push back the limits of what is tolerable and acceptable in established protest patterns. Those limits are what maintains the status quo. And just as the scope of the Yellow Vests movement quickly exceeded the question of the price of fuel, one inevitably begins to hope that Sainte-Soline marks the expansion of the struggle’s imaginary beyond the sole question of the basins.

What is this ‘beyond’? That of a more generalized revolt? Does the contagious emotion that allowed us to cross several lines of gendarmes in the three processions of Sainte-Soline tell us something about what we can expect from a major breakthrough, one that might be able to turn the tide?

A revolt is always a point of overflowing beyond all the forces which first composed it, but a revolt which gives itself the means to last, and therefore to become something else, is generally also the result of a long and meticulous work of elaboration, which includes the construction of a language, a repertoire, a grammar. It is the circulation of a common culture between all those who have the desire to seek a path that absolves them of the identity that has shaped them. On this path, questions appear regarding territories, social determinisms, gender, power relationships, and so forth. So many questions, impossible to sweep away with a wave of the hand, which draw the contours of what could be the camp of those who revolt.

If the revolutionary question arises after a weekend like the one of Saint-Soline, it is not because a lovely tactical move was accomplished. The question arose, unconsciously or not, in the unexpected experience of an asymmetrical balance of power that was nevertheless reversed, in the diffuse feeling of thousands of souls who experienced a power that continually thwarted both the army of gendarmes facing us and the ideologies that almost systematically neutralize any possibility of victory (even an ephemeral one). What prevailed in Sainte-Soline was determination in action, by farandole or by rain of rocks, and the celebration of the feeling of having accomplished something important. It was both DETERMINED AND FESTIVE. It was also the energy of all the initiatives that allowed us to take care of each other, to look after the bruised bodies, and afterwards to accompany those that the gendarmes took away and to stand up against the flood of lies that our enemies poured out to save their own skins. What history has shown us is that a revolution requires a little bit of all of this, on a much larger scale.

The emotion that ran through the weekend of October 29 and 30 teaches us something precious about our ability to stand together in the face of capitalist adversity and our ability to strike back. In the coming months, it is this collective emotion that we want to summon again to put an end to these projects. But we have the right to expect that this particular energy will not be concentrated only in the battle waged in the Deux-Sèvres, that we will not throw all our forces into one and the same struggle only to find ourselves helpless when it comes to an end, whatever the outcome.

Disaster today is everywhere, to the point of not knowing where to turn, and the task of trying to repair the innumerable errors that human beings have accumulated often seems out of reach. Yet front lines are appearing and, however modest they may be in the face of the extent of the catastrophe, they call out to be joined. The fight against the mega-basins is one of them. It has even become, along the way, a serious rallying point. We will certainly need others to extend the threat and spread our forces to new horizons.

No basarran!

This refers to the color of the soil around Sainte-Soline (-trans.)

Uprisings of the Earth, Basins No Thanks, and the Peasant Confederation

Poitou is a former province. The province system organized parts of the French kingdom before it was abolished in the French revolution and replaced with the current system of departments. Some provinces can linger as fairly strong cultural markers. (-trans.)

Zone à défendre (Zone to defend), a phrase now widely used in France to refer to camps constructed in opposition to large infrastructure projects, referencing the most well known zad at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, which successfully prevented an airport from being built after roughly a decade of opposition (-trans.)