As Eduardo Galeano wrote, for centuries South America has been subject to the plunder of its resources, the despoliation of its environment, and the decimation of its peoples. This colonial legacy extends well into the present, particularly in the form of ongoing extraction of natural resources led by multinational corporations.

On December 15, the provincial government in Chubut, Argentina suddenly passed a law that would allow new mining ventures in the southern province. In response, protests immediately broke out in the streets among local people opposed to this development. They erected barricades, clashed with the police, and set government buildings ablaze in the provincial capital of Rawson.

Chubut residents have opposed the Navidad silver mine, owned by Pan American Silver, for years, as well as the government’s repeated attempts to circumvent the existing law prohibiting exploration in the region. A series of anti-mining protests in 2012 also converged on Rawson, and the company and government were forced to scrap their plans to exchange clean water for expensive minerals. In March 2021, protestors chased President Alberto Fernandez and Provincial Governor Mariano Arcioni out of Lago Puelo with stones and shouts of “no is no,” because of their renewed mission to hand the land over to Pan American Silver.

As we write, the people of Chubut have once again pushed the forces of ecocide into retreat. Surprised by the most recent explosion of popular fury, the government backtracked and repealed the new mining law within the week—to the great disappointment of companies like Pan American Silver.

Little to nothing has been reported of this victory in the English-speaking world. Seeing images of the rebellion circulate on Twitter, we got in touch with a friend on the ground to find out more. In their story, we see threads of contemporary revolt woven together: decolonial uprisings and territorial defense, ecological concerns over water and pollution, and the rebuke of government corruption that has animated many global revolts since 2008.

This interview was conducted on December 20, 2021.

I want to start with a question to give some context about the current anti-mining struggle in Chubut Province. Since the new mining exploration zoning law was passed on December 15 by the Chubut Provincial Legislature, there has been a series of protests and clashes with police in Rawson. What is the new zoning law and when did opposition to it begin?

The new law allows Pan American Silver Corporation (based in Vancouver, Canada) to extract minerals from the central area of the province. The project was proposed a long time ago and opposition to it began then. I moved to Rawson from Buenos Aires about eight years ago, but I know it all started before then. There is a law (Ley N° 5001) that establishes that mining activities are prohibited here, but the government clearly didn’t care.

What would the environmental impacts of expanded mining in the Central Plateau be? You mentioned fighting for clean water earlier.

The thing is that here in Chubut we have just one river, the Rio Chubut. All the cities and towns here get water from the river. When it rains too much and the river gets dirty, we don’t have water because purification plants aren’t capable of cleaning it properly. On top of that, mostly during the summer, houses don’t get water for several hours a day. The province is in a water emergency. Epuyen, Comodoro, Puerto Madryn, Playa Unión, Yala Laubat, Piramides, and many other cities struggle with this. If we don’t have enough water to meet our daily needs now, what are we gonna do after new mining projects begin?

I remember one time a few years ago when we couldn’t get water for almost an entire month. And we all know about the toxic chemicals used for mining.1 I’ve read that mining would consume forty percent of the river’s flow.2 Even if the zoning takes place just in the center of the territory, we are all gonna be affected.

We've had difficulties finding information on the history of opposition, which makes it seem as if protests emerged over night. The zoning law was passed earlier than expected by the government and people gathered almost immediately in the government district. How did the latest protests in Rawson and Chubut Province begin? How were people able to mobilize so quickly?

Well, I don’t know how things work in the US, but here when the legislature meets it has to be public and neighborhood assemblies must be able to participate. This time it wasn’t like that. Legislators met without telling us, we weren’t aware so we couldn’t participate, and then out of nowhere we found out that the law was passed. People were obviously angry because what they did was illegal. We felt betrayed. So that same day, I think it was around 8pm, neighbors gathered to protest. It began calmly but then the repression started. People from some neighborhoods say that they heard the police shooting rubber bullets and tear gas until 4am.

When people gathered on December 15 and 16, public buildings were attacked, police cars were set on fire, and the governor’s mansion was burned. Was there a moment when the crowd realized it was going to fight the police and try to storm government buildings? In what order did the events unfold?

I wasn’t there for the December 15 protests, but I was there on December 16. We met outside the governor’s mansion and police were all over the place. They weren’t on the same street, but they were surrounding us. I was standing next to a window and then a bunch of people arrived together so I walked away to take some photos. When I got back to the window, it was broken and people were throwing branches inside. I started to pay closer attention to what was going on around me because we all knew things were gonna get heavy at some point in the day. I saw people running towards the opposite corner of the street, mostly men, so me and my family went to the back of the crowd. After the governor’s mansion was set on fire, we were standing near the back and suddenly people started to run towards us because the police had arrived and they were shooting rubber bullets.

How did you know things would get heavy at some point during the day?

Well, people were furious. We all were. We didn’t want to do things peacefully this time. I guess we all felt the same. We wanted to break things. The government didn’t hear us, so we wanted to force them to do it. So we did.

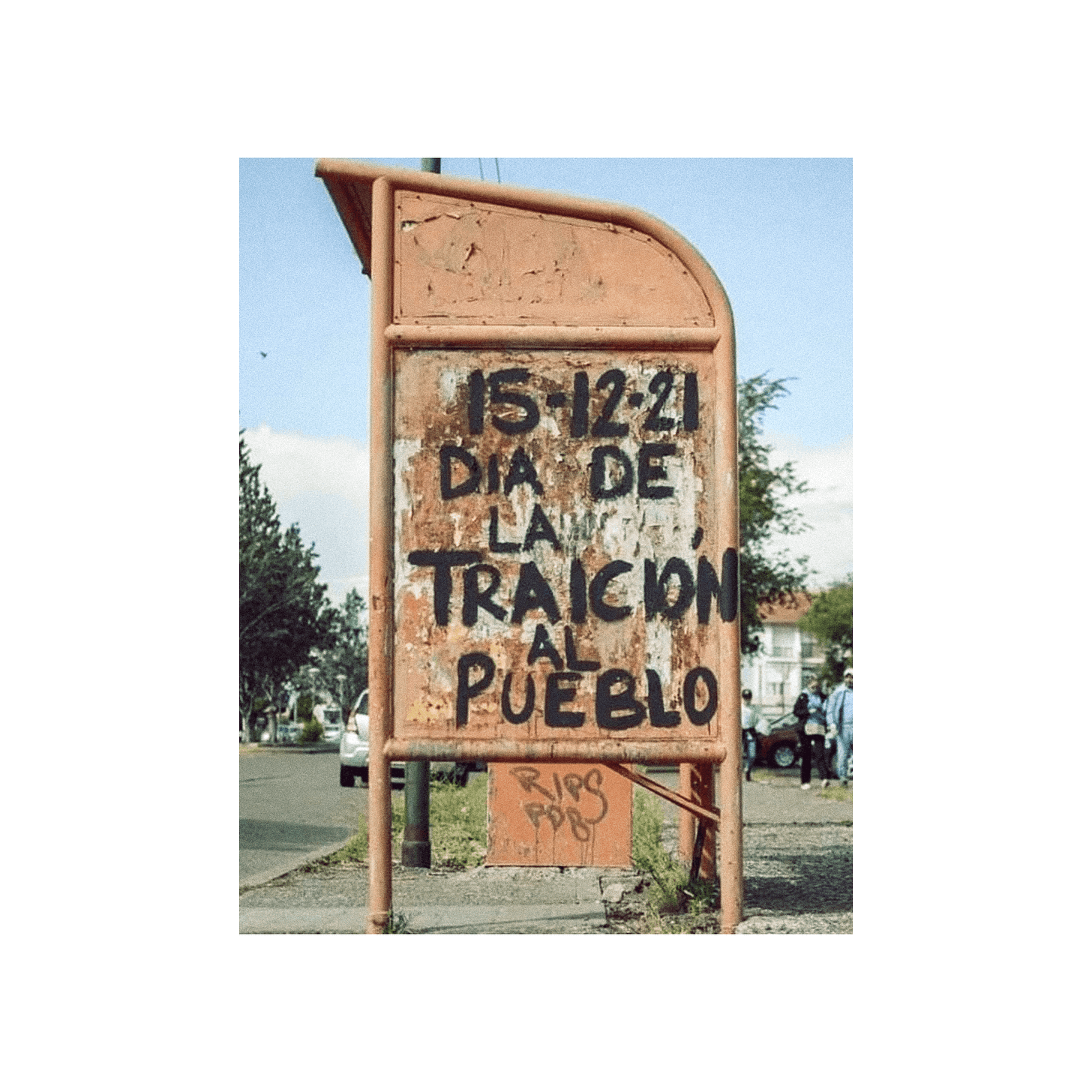

We understand that feeling. What slogans, graffiti, or banners have you been seeing? What have people been screaming in the streets?

Most graffiti says things like traidor. Let me explain: when Arcioni (the Provincial Governor) was advertising his campaign during the elections, he said he was part of the opposition and that he wouldn’t allow mining activities in the area. That’s why people voted for him. I also see a lot of banners that say el pueblo despertó (“the people have woken up”) and estudia, no seas policía (“study, don’t be a cop”).

Have you seen much tactical creativity or innovation? What’s new about this cycle of struggle for you and your comrades?

Sadly, I think violence was necessary. We got attention from the media and the government—something that has never happened before. On top of that, since more people became aware of the problem, we received support from workers’ unions and they joined the protests. Here in Chubut, the main sources of income are petroleum and fishing. The workers from the port of Rawson stopped working and said they’re not going back to work until the law is repealed. It pressured the government to do things quickly because now they know that if they don’t hear what we’re saying, we’re not gonna be quiet and calm about it.

The violence got our attention too. But there’s been barely any English language coverage, which is disappointing.

There’s barely any coverage from Argentina's national media either.

One amazing thing about struggles like this is that our common humanity reemerges and we find that our relationships with strangers grow more supportive and joyful. Can you recall any moments of individual bravery or kindness or moments in which people helped one another?

Yes, that’s something that makes me so emotional. I see things like this everyday, even in minor actions. For example, the other day when we were running from the police, this guy passed by us and he dropped his wallet. All of a sudden the corner was full of people screaming and calling to him. It’s something dumb, but it makes you feel that people are united.

Today I almost cried actually. Like I said before, the opposition started years ago, and many people only became aware recently. So the “leaders” have been fighting almost completely alone since then. One of them was hunted by the police—I think she was in jail for a couple of days and was a victim of police violence for such a long time. Today when I was standing in the crowd with so many people and we were all singing, I saw her standing there crying. It made me want to cry too because she finally feels that she’s not alone and that there’s people who have her back.

That’s beautiful—thanks for sharing. Moments when we help each other escape police violence and arrest are really powerful and create very special relationships. You also mentioned that the demonstrations include “leaders” who have been fighting mining for a long time. What do you mean by "leaders"? Why did you put that in quotation marks?

I put it in quotation marks because I’m not sure that’s the right thing to call them. They’re the ones who organize the protests (days, hours, places) and also the ones who gather signatures and participate in government activities (like the public sessions).

Several arrests have been made this week and the police have announced investigations into Wednesday night’s property destruction. Protesters have left demonstrations with injuries from rubber bullets and tear gas. What has the police response been like? How has it compared with past cycles of struggle?

Well, past cycles were peaceful so the police weren’t present. Now they are brutally violent. If I have to be honest, I hate them. People sometimes say that they’re only doing their job, but being there you can tell that they seem to enjoy it.

One of my classmates was running from them the other day and stopped to help an older lady. This policeman started yelling at my friend asking, “What the fuck are you doing here, why did you even come?” She obviously replied in a rude way, yelling back, “Yuta de mierda la concha de tu madre” [Use your imagination, but something like: fuck you, you motherfucking cop–Eds.]. Then the police officer shot her twice in the leg.

After protestors set government buildings on fire, the police were going around town in cars shooting random people who were walking on the streets. Even if they weren’t doing anything, cops started to shoot at everyone.

I think I get the gist of what your friend said: fuck the police. They’ll always be on the wrong side of the barricades. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk in the middle of all of this. I just saw the news that the government backtracked on the mining law. Congratulations. Hope you all keep going and make sure they follow through!

Thank you. They repealed the law in the morning. We’re so happy and definitely gonna keep going!

The chemical being considered for use in Pan American Silver Corporation’s Navidad silver mine is xanthate. When a copper mining dam burst in Chile in 1997, xanthate and sulfuric acid were released into the Loa River, making it toxic and uninhabitable.

Laura Rocha, “In an unexpected session, Chubut approved mega-mining on the plateau,” Infobae, December 15, 2021.

Eighty percent of Chubut River’s flow is currently consumed by drinking water and agriculture. The project would endanger the Sacanana Basin, a reservoir already being depleted by climate change. Ibid.