Editor’s Preface

During a recent trip to the archives, I came across a long out-of-print book penned by the late SDS leader Tom Hayden. He is one of the best-known figures from the American Sixties, although he is rarely read these days except as a dose of nostalgia. Flipping through the book got me thinking about his tumultuous era: where might all that revolutionary energy have gone, had the arc of history bent otherwise? I was surprised to encounter, tucked into the volume’s conclusion, some ideas whose contemporary relevance struck me as almost uncanny. Excited by this chance find, I’ve reproduced an excerpt below in order to make the text accessible for a wider audience today.

Hayden’s short book Trial, first published in 1970, is primarily an analysis of the infamous case of the Chicago Eight—an odd assortment of radicals and provocateurs, author included, charged with federal crimes in the wake of the 1968 DNC protests. It’s an interesting read, first as historical document and also as eerie foreshadowing of the repression many are already facing for their participation in the George Floyd Rebellion.

But I think it’s the last chapter which is the most relevant for us today. In the book’s closing pages, Hayden searches for a revolutionary way forward given that the mass movements of the previous decade were waning and reaction was setting in. He describes his vision of a New American Revolution: a vast uprising bringing together national liberation movements, Black Power, and a heady mix of student radicalism and the counterculture. It’s a theory of revolution born from the failures of the Sixties—not a fully developed strategy, not equally convincing in all its claims, but a line of thought which may hold lessons for us fifty years later.

While certain terminology feels dated, Hayden’s voice is still fresh and the clarity of his argument is striking. Its central thesis runs something like this. If waves of mass protest alongside moments of fierce resistance—the Sixties having an abundance of both—were insufficient to bring about revolution, then a revolutionary process will also require the creation of “new centers of power” where dedicated groups of people actively build new forms of collective life. The democratic bodies developed this way would be the same self-governing institutions of the future liberated society. ‘Revolution’ could then be understood as the growth of these novel arrangements and their gradual or sudden displacement of existing power structures. This is dual power, in short—a term Hayden explicitly uses here.

Given the ongoing George Floyd Rebellion, I should note that the first guiding principle Hayden offers for this coming revolution is self-determination for people of color. While the language of “internal colonies” is no longer in fashion, his description of the structural inequities facing many communities sadly remains true and his appeal to self-determination remains powerful. As Hayden provocatively argues regarding the radical movements of his time, the idea that Black, Puerto Rican, Chicano, and Indigenous liberation simply means integration into the so-called “American way of life” is a lie sold by the white, liberal establishment. Then as now, they will inevitably see in the shards of a smashed window the frustrated desire to participate in their system rather than the will to destroy, escape, or transform it.

The second principle Hayden outlines is the creation of “free territories,” a concept which has echoes in the autonomous zones spreading today as well as significant overlap with the current of radical municipalism popular in recent years. A free territory is a physical space, like an urban neighborhood or rural commune, where people collectively fashion a new social order in contrast to mainstream society. Importantly, these are not escapist playgrounds—a charge Hayden levels against many of his drop-out peers—but embodied attempts to depose governmental authority at its most basic level, that of everyday life. In Hayden’s revolutionary scenario, a network of free territories would become the ‘new centers of power’ which would have both the vitality and the force to finally overcome the old world.

Hayden’s lost vision of a New American Revolution may have gone unrealized in his lifetime, but the strategic course it charts and the revolutionary promise it contains may still speak to us today. I hope you find this archival text to be of interest and inspiration as we seek our own paths in building and fighting for new worlds.

The New American Revolution: An Excerpt from Tom Hayden’s Trial

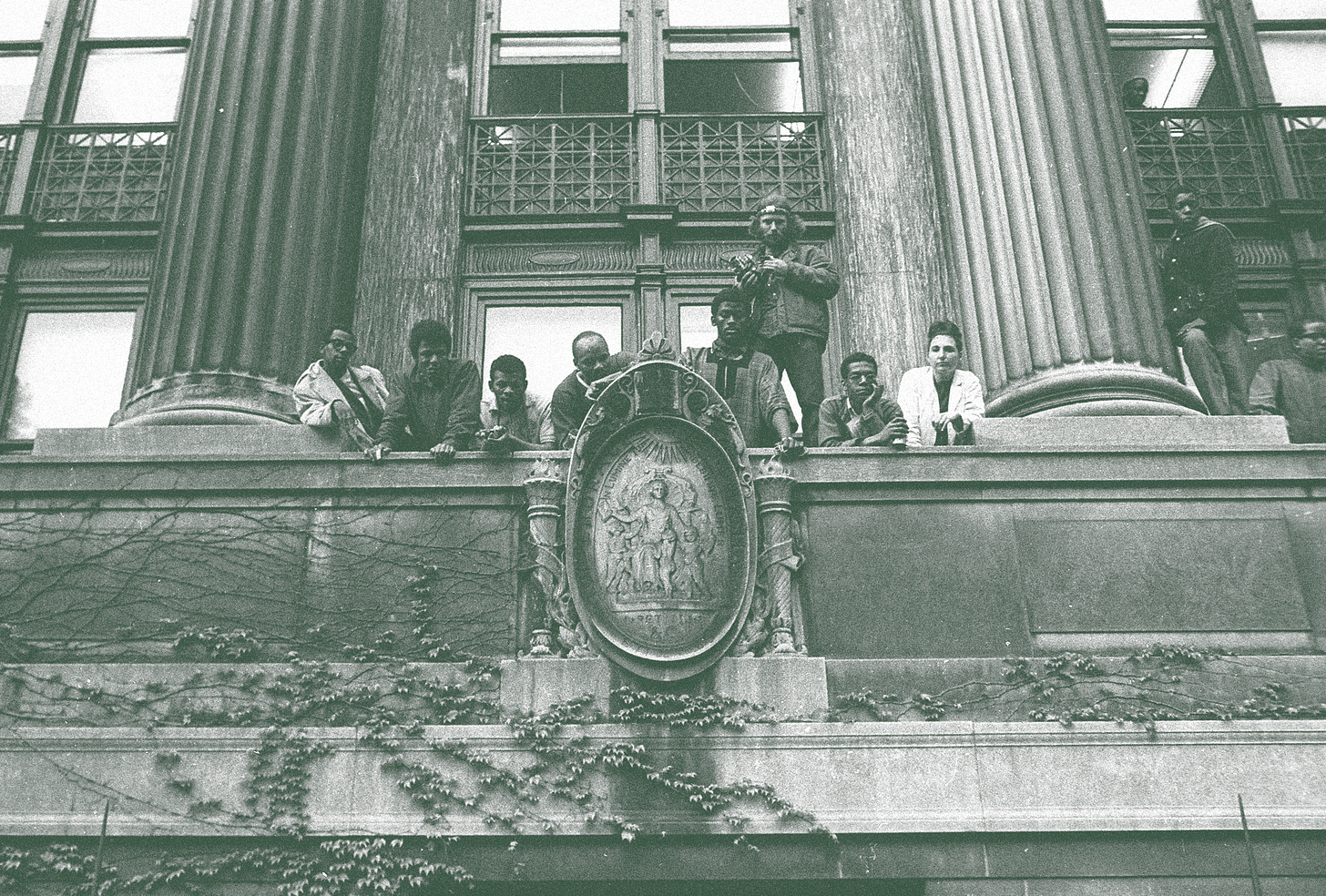

If we look at any revolutionary movement, we see that it evolves through three overlapping stages. The first is protest, in which people petition their rulers for specific policy changes. When the level of protest becomes massive, the rulers begin to apply pressures to suppress it. This in turn drives the people towards the second stage, resistance, in which they begin to contest the legitimacy of the rulers. As this conflict sharpens, resistance leads to a liberation phase in which the ruling structure disintegrates and new institutions are established by the people. America in the Sixties experienced primarily the protest phase, but resistance has already become commonplace among the blacks and the young. Temporary periods of liberation have even been achieved—as when students occupied Columbia University for one week and learned they could create new relationships and govern themselves. Of course, these experiences only provide a glimpse of liberation as long as the government has sufficient police power to restore university officials to office.

In the resistance phase it becomes necessary to lay plans for defeating the police and building a new society. It is a time of showdown in which the government will either crush the resistance and restore its own power, or undergo constant failure, eroding its own base to a very dangerous point. Because it challenges the legitimacy of the way things are ordered, resistance acquires the responsibility of proposing and creating new arrangements.

The general goals of American revolutionaries are not too difficult to state. We want to abolish a private property system which, in its drive for new markets, benefits only a few while colliding violently with the aspirations of people all over the world. We want a transformation in which the masses of people, organized around their own needs, create a new, humane, and participatory system.

What is less clear is the kind of structural rearrangement that will be required to achieve these goals. A radical movement always begins to create within itself the structures which will eventually form the basis of the new society. So it is necessary to look at the structure of motion-now-in-progress to understand what must be destroyed and what must be built. We need a new Continental Congress to explore where our institutions have failed and to declare new principles for organizing our society.

The first principle of any new arrangement is self-determination for our internal colonies. In the Seventies the Third World revolutions will sharpen not only on other continents but here inside the US. The black ghettos are a chain of islands forming a single domestic colony. The same is true of the Puerto Rican people struggling for independence in San Juan, New York, and Chicago; the Chicano people of the Southwest; and the Asians and Indians struggling in their small urban and rural communities. The concept of "integration," which so dominated consciousness in the Sixties, is now blinding most people to the new reality of self-determination. Underlying the desire for integration is the even deeper belief that America is "one nation, indivisible." It seems unthinkable that this country might literally be broken up into self-determining parts (nations on the same land), yet that is more or less what is evolving. The failure of the US to make progress in the areas of education, jobs, housing, and land reform here at home, the constant recourse to repressive violence at a time when the "revolution of rising expectations" is nowhere stronger than in America, can only make Third World people turn towards independence.

The second principle of rearrangement should be the creation of Free Territories in the Mother Country. Already we are seen as alien and outside White Civilization by those in power. It is necessary for us to create amidst the falling ruins of this empire a new, alternative way of life more in harmony with the interests of the world's people.

Abbie [Hoffman] is a pioneer in this struggle, but so far "Woodstock Nation" is purely cultural, a state of mind shared by thousands of young people. The next stage is to make this "Woodstock Nation" an organized reality with its own revolutionary institutions and, starting immediately, with roots in its own territory. At the same time, the need to overcome our inbred, egoistic, male, middle-class character, and especially to create solidarity with Third World struggles, has to become a foremost part of our consciousness.

The new people in white America are clustering in ghetto communities of their own: Berkeley, Haight-Ashbury, Isla Vista, Madison, Ann Arbor, rural Vermont, the East Village, the Upper West Side. These communities, often created on the edge of universities, are not the bohemian enclaves of ten years ago. Those places, like Greenwich Village and North Beach, developed when the alienated were still a marginal group. Now millions of young people have nowhere else to go. They live cheaply in their own communities; go to school or to various free universities; study crafts and new skills; learn self-defense; read the underground press; go to demonstrations. The hard core of these new territories is the lumpen-bourgeoisie, drop-outs from the American way of life. But in any such community there is a cross-section of people whose needs overlap. In Berkeley, for example, there are students, street people, left-liberals and blacks, together constituting a radical political majority of the city. Communities like this are nearly as alien to police and "solid citizens" as are the black ghettos.

The importance of these communities is that they add a dimension of territory, of real physical space, to the consciousness of those within. The final break with mainstream America comes, after all, when you literally cannot live there, when it becomes imperative to live more closely with "your own kind."

Until recently people dropped out in their minds, or into tiny bohemian enclaves. Now they drop out collectively, into territory. In this situation feelings of individual isolation are replaced by a common consciousness of large numbers sharing the same needs. It is possible to go anywhere in America and find the section of town inhabited by the drop-outs, the freaks, and the radicals. It is a nationwide network of people with the same oppression, the same institutions and language, the same music, the same styles, the same needs and grievances: the very essence of a new society taking root and growing up in the framework of the old.

The ruling class views this pattern with growing alarm. They analyze places like Berkeley as "red zones" like the ones they attempt to destroy in Vietnam. Universities and urban renewal agencies everywhere are busy moving into and destroying our communities, breaking them up physically, escalating the rents, tearing down cheap housing, and replacing it with hotels, convention centers, and university buildings. Politicians declare a "crime wave" (dope) and double the police patrols. Tens of thousands of kids are harassed, busted, moved on.

* * *

In every great revolution there have been such "liberated zones" where radicalism was most deeply rooted, where people tried to meet their own needs while fighting off the official governing power. If there is revolutionary change inside the Mother Country, it will originate in the Berkeleys and Madisons, where people are similarly rooted and where we are defending ourselves against constantly growing aggression.

The concept of Free Territories does not mean local struggles for "community control" in the traditional sense—battles which are usually limited to electoral politics and maneuvering for control of funds from the state or federal government. Our struggles will largely ignore or resist outside administration and instead build and defend our own institutions.

Nor does the concept mean withdrawal into comfortable radical enclaves remote from the rest of America. The Territories should be centers from which a challenge to the whole Establishment is mounted.

Such Free Territories would have four common points of identity:

First, they will be utopian centers of new cultural experiment. "All Power to the Imagination" has real meaning for people experiencing the breakdown of our decadent culture. In the Territories all traditional social relations—starting with the oppression of women—would be overturned. The nuclear family would be replaced by a mixture of communes, extended families, children's centers, and new schools. Women would have their own communes and organizations. Work would be redefined as a task done for the community and controlled by the workers and people affected. Drugs would be commonly used as a means of deepening self-awareness. Urban structures would be destroyed, to be replaced with parks, closed streets, expanded backyards inside blocks, and a village atmosphere in general would be encouraged. Education would be reorganized along revolutionary lines, with children really participating. Music and art would be freed from commercial control and widely performed in the community. At all levels the goal would be to eliminate egoism, competition, and aggression from our personalities.

Second, the Territories will be internationalist. Cultural experiment without internationalism is privilege; internationalism without cultural revolution is false consciousness. People in our Territories would act as citizens of an international community, an obstructive force inside imperialism. Solidarity committees to aid all Third World struggles would be in constant motion. Each Territory would see itself as an "international city." The flags, music, and culture of other countries and other liberation movements would permeate the Territory. Travel and "foreign relations" with other nations would be commonplace. All imperialist institutions (universities, draft boards, corporations) in or near the Territory would be under constant siege. An underground railroad would exist to support revolutionary fugitives.

Third, the Territories will be centers of constant confrontation, battlefronts inside the Mother Country. Major institutions such as universities and corporations would be under constant pressure either to shut down or to serve the community. The occupying police would be systematically opposed. Stores would be pressured to transform themselves into community-serving institutions. Tenant unions would seek to break the control of absentee landlords and to transform local housing into communal shelter. There would be continual defiance of tax, draft, and drug laws. Elected officials would serve the community or be challenged by parallel structures of power. Protest campaigns of national importance, such as the anti-war movement, would be initiated from within the Territories. The constant process of confrontation would not only weaken the control of the power structure, but would serve also to create a greater sense of our own identity, our own possibilities.

Fourth, they will be centers of survival and self-defense. The Territories would include free medical and legal services, child-care centers, drug clinics, crash pads, instant communication networks, job referral, and welfare centers—all the basic services to meet people's needs as they struggle and change. Training in physical self-defense and the use of weapons would become commonplace as fascism and vigilantism increase.

Insurgent, even revolutionary, activity will occur outside as well as inside the Territories. Much of it will be within institutions (workplaces, army bases, schools, even "behind enemy lines" in the government). But the Territories will be like models or beacons to those who struggle within these institutions, and the basic tension will tend always to occur between the authorities and the Territories pulling people out of the mainstream.

The Territories will establish once and for all the polarized nature of the Mother Country. No longer will Americans be able to think comfortably of themselves as a homogeneous society with a few extremists at the fringes. No longer will politicians and administrators be able to feel confident in their power to govern the entire US. Beneath the surface of official power, the Territories will be giving birth to new centers of power.

In the foreseeable future, Free Territories will have to operate with a strategy of "dual power"—that is, people would stay within the legal structure of the US, involuntarily if for no other reason, while building new forms with which to replace that structure. The thrust of these new forms will be resistance against illegitimate outside authority, and constant attempts at self-government.

Mother Country radicalism will have its unique organizational forms. Revolutionary movements have turned towards the concept of a centralized, disciplined, nationally-based "vanguard" party which leads a variety of mass organizations representing specific interests (women, labor, students, etc.). This organizational form is logical where people are already disciplined by their situation (as in a large factory) or where the goal is "state power." But it is not so clear that such an organizational form is necessary—at least now—for Mother Country radicalism. Certainly the excessive individualism and egoism which dominate the culture of young people must be overcome if we are going to survive, much less make a revolution. But the organizational form must be consistent with the kind of revolution we are trying to make. For that reason the collective in some form should be the basis of revolutionary organization.

A revolutionary collective would not be like the organizations to which we give part-time attachment today, the kind where we attend meetings, "participate" by speaking and voting, and perhaps learn how to use a mimeograph machine. The collectives would be much more about our total lives. Instead of developing our talents within schools and other Establishment institutions, we would develop them primarily within our own collectives. In these groups we would learn politics, self-defense, languages, ecology, medical skills, industrial techniques—everything that helps people grow towards independence. Thus the collectives would not be just organizational weapons to use against the Establishment, but organs fostering the development of revolutionary people.

The emphasis in this kind of organization is on power from below. It begins with a distrust of highly centralized or elite-controlled organizations. But we should also recognize that decentralization can degenerate into anarchy and tribalism. Collectives must stress the need for unity and cooperation, especially on projects which require large numbers or when common interests are threatened. We should seek the advantages of coordinated power while avoiding the problem of an established hierarchy. A network of collectives can act as the "revolutionary council" of a given Territory and a network of such councils can unite the Territories across the US. In addition to such political coordination, the Territories can be united through the underground press and culture, through conferences and constant travel.

* * *

Finally and above all, the concept of Free Territories does not imply that the youth movement is already "revolutionary," except in its potential. Free Territories are only a form in which the struggle goes on. Both the "student movement" and the "youth culture" still must deal with the permeation of white, male, middle-class attitudes. Neither students on strike nor stoned freaks in the street constitute a real revolutionary force. There must be still more transformation of our character on all levels. Male chauvinism must be overthrown in the political movement and the rock culture; individualism and egoism must be replaced by a collective spirit; narrow, middle-class demands for privilege must be replaced by demands in the interest of the taxpaying masses.

Such a transformation might seem impossible in the Western cultural context of “rugged individualism,” comic book cowboys, and Dick Tracy. If our generation has produced one classic political type, it is Macho Man, the swaggering, aggressive political or cultural hero. This personality type is pernicious to revolutionary change because it is driven by the same status needs that pervade the larger society. Not only does this ego-tripping contradict revolutionary values, but it becomes suicidal in a period of approaching fascism. In a time of resistance and extra-legal activity, with agents everywhere, there is no outlet for those who must tell the world (or at least their “chicks”) of their feats. We need a “revolution in the revolution” to deal with this continuing arrogance.

The most burning need for a change in our attitude lies in our relationship to Third World liberation struggles. The creation of Free Territories in the Mother Country is not separate from the national liberation battles of Third World people. The Territories are a way to prepare for the vast international uprising which will be the next American Revolution.

We must not follow the chauvinist path taken by the Left in other colonial periods. Our support for black liberation must be unconditional. We must begin by making it clear that there will be no racism and no racist escapism in the peace movement or in Woodstock Nation. If we are serious about becoming new men and women, free of the bloody legacy of white American civilization, then we have the responsibility of becoming the first white people in history to live beyond racial definitions of interest. There is something racist about “Woodstock Nation”—not the familiar racism of George Wallace, but an attitude of distance that comes from living in the most comfortable oppression the world has ever known. We are constantly in danger of escaping into a cultural revolution of our own, a tiny island of post-scarcity hedonism, pacifism, and fantasy far from the blood and fire of the Third World.

White radicals can follow the path of their own legitimate revolution, however, without abandoning the Vietnamese and the blacks. In fact we cannot realize our own needs without the destruction of the same colonial system that brutalizes the Third World. We are at one end of a line of resistance whose other end is rooted in black America and the Third World. Young white people today, whether working-class or middle-class, are the first privileged generation with no real interest in inheriting the capitalist system. We have experienced its affluence and know that life involves far more than suburban comfort. We know further that this system contains its own self-destruct: racism, exploitation, and militarism lead nowhere in the contemporary world but to war and waste. As we look out over the top of imperialism we should be able to see that our true allies are those who live below and beyond its privilege, the wretched of the earth.

Certainly there is a gap between the children of affluence and the children of squalor. Our need for a new life style, for women's liberation, for the transformation of work, for a new environment and educational system, cannot be described in the rhetoric of Third World revolution where poverty, exploitation, and fascist violence are the immediate crisis. We cannot be black; nor can our needs be entrusted to a Third World vanguard of any kind.

But our destiny and possible liberation cannot be separated from the Third World vanguards. The change toward which we are inevitably moving is one in which the white world yields power and resources to an insistent humanity. There is no escape—either into rural communes or existential mysticism—from this dynamic of world confrontation. By our deeds each day we are determining what role, if any, we will have in the world's future. What we have and have not done, for Bobby [Seale], and for Cuba, and for Vietnam, measures exactly our stature in the new world being created.

Some will cry that this cosmic formulation denies the issue of priorities. How shall it be settled whether to work first against racism, or the war, or male supremacy, or the production speed-up? Historically the white Left has argued that colonial liberation should wait for socialist revolution or be submerged in a black-white working-class coalition. In the same vein, some Panthers today argue that the women's movement should wait until blacks are liberated. Special interests seem constantly in danger of being betrayed, and so we fragment into groups with particular, immediate priorities.

At first this fragmentation appears hopeless. But the fact that so many different people are moving at once for their own liberation suggests an inspiring possibility. We are living in a time of universal desire for a new social order, a time when total revolution is on the agenda: not a limited and particular "revolution" for national identity here, for the working class there, for women here—but for all of humanity to build a new, freer way of life by sharing the world's vast resources equally and fraternally. The world's people are so interdependent that a strike for freedom anywhere creates vibrations everywhere. The American empire itself is so worldwide in scope that humanity has for the first time not only a common spirit but a common enemy. Through their particular struggles, more and more revolutionaries see the possibilities of the "new man" envisioned by Che Guevara. Formed in an international upheaval, such a human being would be universal in character for the first time in history. To become such a whole person in the present means fighting not only around immediate self-interest but against all levels of oppression at once.

It is in this context that priorities, especially the priority of Bobby Seale's trial, should be understood. Vanguards will be discovered in action, and priorities will be created where total showdowns between the status quo and revolution appear. Bobby's case, and the repression of the Panthers generally, embodies just such a showdown. Bobby and the Panthers were the first to raise the battle cry of liberation inside America, the first black revolutionary party with an internationalist perspective, the first to threaten imperialism totally from within. The US government certainly sees the Panthers this way; that is why it is attempting, through Bobby's trial, to demonstrate that genocide awaits all who rebel. All those who value their own liberation must go with the Panthers and Bobby as they become symbols of humanity making a time-honored stand: Freedom or Death.

A Note on the Text

I have reproduced the second half of chapter 16, “The New American Revolution,” from Tom Hayden’s book Trial (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970). I have omitted the first portion of the chapter, largely dealing with the specific political situation at the time, which I do not consider to be as directly relevant today. An earlier version of Hayden’s essay was first published in the July 1970 issue of Ramparts and contains slight variations from the later book edition.